Rethink Pyeongsaengdo, the Life Course Painting

Capturing a Joyful Moment of a Personal Life Lee Sukyung, Curator, National Museum of Korea

A series of paintings that depict celebratory occasions in private life and meaningful events as a public official, from passing the State Examination moving through low official positions to high official positions have been passed down from the Joseon dynasty (1392-1897). Private occasions consist of the first birthday celebration, the wedding ceremony and the sixtieth wedding anniversary celebration. On the other hand, public official occasions include the celebration of the passing of the State Examination, processions with a ride on horses or sedan chairs that suit their official posts, and enjoying easygoing times after resignations. These scenes are painted on 8-12 long sheets of silk or paper with a height that is appropriate for a folding screen, comprising of one set. The 26 paintings, the majority of which consist of 8 panels handed down until today are assumed to have been created after the 19th century to the early 20th century. The tradition of painting important events in the biographies of the saints, such as Buddha and Confucius, throughout various scenes exists in Korea, China and Japan, but the custom of painting the personal life of on individual in many different scenes is only found out in Korea. They show a wishful joyous moment from childhood to senescence that can be enjoyed by the upper class in Joseon.

Paintings that Show Many Subjects but Require Much Concern

Since they depict personal celebratory occasions or the processions of high-rank officials, people and objects responsible for many different roles appear in them. These paintings enable us to find out about life in the 19th century. They hold high significance as the visual materials that vividly deliver scenes from the first birthday celebration, the sixtieth wedding anniversary celebration, the procession of the Senior First official, and the procession for an appointment as a provincial governor. Unfortunately, some details regarding them are indistinct for understanding. First, we do not know what these paintings were called in the Joseon era. The current name, “pyeongsaengdo,” can be only found in the records dated from the early 20th century. A specific name to label these painting may not have existed in the Joseon period. The text by Yi Chae (1745-1820), a literati official in the late 18th century, which he wrote after viewing the painting consisting of 8 panels with respect to life as a government official of his acquaintance, Seo Gansu (1734-?) is handed down as part of his writing collection. This text suggests that the paintings of this folding screen are comprised of the scenes as to the life of a public official such as studying at a village school, preparing for the State Examination, winning first place in the Examination, an appointment as a low and local official, and a resignation by Seo Gansu. These scenes mostly correspond to those regarding the public official in the paintings called “pyeongsaengdo,” but Yi Chae only titled these paintings as “the Folding Screen with Paintings for Seo Gansu,” implying that no specific name to refer to these paintings did exist at the time.

Why Pyeonsaengdo are Related to Specific Figures and Painter

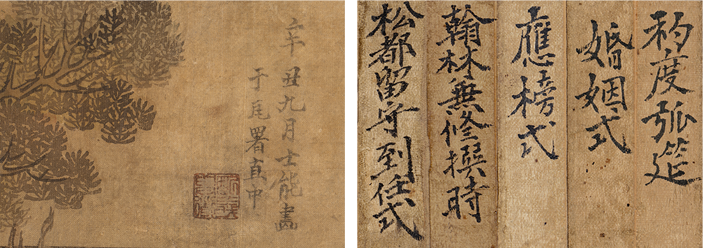

However, in the 20th century we begin to call these paintings “pyeongsaengdo,” and consider that Kim Hongdo (1745-after 1806), a painter from the Bureau of Paintings of the Joseon dynasty and the representative artist of the late 18th century started painting pyeongsaengdo. The National Museum of Korea (“NMK”) acquired one of these paintings in the 20th century, and this has been restored in the digital format this time. At the time, it was registered it with the name of “Pyeongsaengdo of Modang Hong Isang (1549-1615),” and the last panel of this folding screen included a phrase indicating that it was painted by Kim Hongdo in 1781. Unfortunately, this writing does not indicate a style of handwriting from the 18th century of Joseon. Also it includes a Chinese character that was not used in the Joseon period. In this period, a Chinese character, “畫,” was used to mean “paint” whereas a character, “畵” in the said painting follows the Japanese indication. It is because the phrase was written in the early 20th century when a century elapsed from the time Kim Hongdo worked as a painter.

In addition, each panel of the folding screen includes texts that have been considered the absolute standards to understand the paintings. The times when the texts were written differ from the time when the paintings were created. Whether the titles reflect the intentions of the painters needs to be checked. We can readily presume what the scenes as to personal occasions depict, while the paintings from the 4th panel to 7th panel—Time of the royal archivist and the senior fifth official in the Office of Special Advisors, Arrival Ceremony of the Magistrate of Songdo as the Junior Second, Time of the post of the Minister of Defence as the Senior Second, Time of the post of the Left State Councillor as the Senior First—have been known to depict the life of the public official. Each official who appears in each painting rides a sedan chair or a wagon befitting his title and class explained in the title. A sedan chair driven by two horses in the 5th panel is for provincial governors or secretaries at the second rank or higher. A sedan chair in the shape of a wagon in the 6th panel is the vehicle with one wheel for the officials at the junior second rank or higher. A sedan chair in the shape of a plantain in the 7th panel is for the officials at the junior first rank or higher. It is not necessary to stick to the titles of public officials based on the title written in each panel. It is possible to depict officials who are appointed to different titles of the same rank. In other words, the 7th panel may depict the procession of the Right State Councillor instead of the Left State Councillor. Thus, not every text written in the painting shall be considered helpful and complete information to understand the painting.

*Caption: Since the writing in the 8th panel was included after the folding screen had been created, it was removed for the digital restoration.

The influence of its registration information by the NMK was huge. Throughout the 20th century, these paintings were firmly believed to be created by Kim Hongdo to depict the life of Modang Hong Isang. Although the assumed style of handwriting was not the style from the 18th century, the conclusion was a result of the belief that this information was reliable. However, in the early 2000s, an argument that these paintings are not relevant to the life of Hong Isang and cannot be regarded as works by Kim Hongdo due to the difference of the style of painting. In fact, Hong Isang passed away at 67, failing to enjoy the celebratory event to mark the sixtieth wedding anniversary. He passed the State Examination winning first place and served as the Magistrate of Songdo, but has never been appointed as the Minister of Defence or the Left State Councillor.

As the NMK acquired another folding screen in the mid-20th century, this was named as the Pyeongsaengdo of Hong Gyehi (1703-1771), literati from the 18th century in Joseon. The reason lies on the paper attached to the back of the folding screen with the writing consisting of words such as the Pyeongsaengdo of Hong Gyehi, the Governor of Pyeongan, the cabinet member, the sixtieth birthday celebration, along with the indication that it was painted by Kim Hongdo. However, the description in this paper is different from what has been painted. Hong Gyehi had never served as the Governor of Pyeongan or the cabinet member, and held the sixtieth wedding anniversary celebration.

As stated above, although these texts cannot be deemed to deliver accurate information of the paintings, the subject matter and the painter of them have been decided based on them. These are cases in point that show that texts written in the paintings has such an immense influence on judging the painting in the area of studying traditional paintings. Although these paintings provide much information with many figures and objects, it is difficult to understand them in an appropriate way. The process in which the name and the artist were conferred to in these paintings is as interesting as their details.

Relevance to Kim Hongdo, a Master of Genre Paintings

On one occasion, these type of paintings were named “the genre painting attributed to Kim Hongdo” as they were acquired by the museum. The paintings in the category of Pyeongsaengdo have been perceived as the works by Kim Hongdo or copies of original works by Kim Hongdo. The reason why these type of paintings have been perceived as the works by Kim Hongdo even though there’s no grounds for such an assumption exist lies in the understanding that Kim Hongdo is a master of the genre painting, who was exceptionally good at depicting figures and customs. It has been frequent to sell and purchase genre paintings from the Joseon dynasty as the works by or attributed to Kim Hongdo since the early 20th century.

However, we can find a distinct difference between his works and pyeongsaengdo. The eight-panel folding screen painted by him in 1778 depicts the vivid scenes of life, such as a traveler leaving for their destination and a procession of high-rank officials in the composition of “Z.” Indeed, pyeongsaengdo was painted in the composition of “Z,” as well, yet trees and houses were laid in places to avoid viewers from looking out of the screen, creating an elaborate structure, different from paintings by Kim Hongdo. In addition, the facial expressions of the figures are uniform without the vitality of those in the works by Kim Hongdo. Thus, paintings in the type of pyeongsaengdo have no direct relevance to Kim Hongdo.

The Paintings Filled with the Accomplishments of the Worldly Life

The opinion that relates pyeongsaengdo to specific figures, Hong Isang and Hong Gyehi, and a specific painter, Kim Hongdo is still predominant. An assumption has been suggested: the descendants of Hong Isang requested Kim Hongdo to create paintings that depict the life of Hong Isang so as to raise the family's status and the pyeongsaengdo of Hong Isang that has been handed down today are the re-creation of the original paintings by Kim Hongdo by a different descendant by Hong Isang in the early 19th century. However, such an assumption cannot explain the reason why some scenes do not match the life of Hong Isang. It is also doubtful that his descendants wanted the paintings that depict the glorious life of the public official, which was unrelated to the fact. The accomplishments by Hong Isang, which were recognized at the time, were not a high-rank official: based on the writings recording his life, he was highly thought of due to his royalty and filial duties. During the Japanese invasions of Korea of 1592–1598 or Imjin War, he attended King Seonjo (r. 1567-1608) for an evacuation to Pyeongyang and addressed a memorial to the king for punishing a treacherous subject, which proves his royalty. He had a high reputation for implementing filial duties. He looked for his mother even taking high risks during the Imjin War. The Veritable Record, the first and oldest official record of the Joseon dynasty, includes a description of high reputation for his integrity. Thus, an ideal life of the public official from the prestigious families is not only to reach the high-rank post, but also to gain praise for implementing royalty and filial duties, which are the important values in Confucianism that served as the fundamental principle of Joseon. However, pyeongsaengdo does not display any moral values. It only contains secular achievements.

Who Wanted Such Paintings Depicting Secular Achievements?

Who were the consumers for such paintings that reflect values in pursuit of personal wealth and honor? An opinion that the families who wielded power at the time ordered this type of paintings to raise the reputation of the families based on their consciousness of the noble families is prevailing. In the 19th century, a tendency that some influential families exclusively possessed the power increased. Even though people managed to pass the State Examination in their 30s, not everyone was appointed for public posts. As such, in reality, it was difficult to reach high-rank officials. Thus, these paintings are understood to have been consumed by a few influential families. However, a question as to whether this would be indeed true is raised. Did the highest class who were already equipped with wealth and honor need the folding screen that depicts secular accomplishments in such an obvious way? Since they already achieved the life of the high and distinguished official that is pursued in pyeongsaengdo, they may not have needed to dream about it. Rather, would it be possible that those who intended to purchase the paintings were people who became the nobleman through a rise in status? In the Joseon period, there was a system that allowed people to pay money to the country for the purpose of a rise in status. A number of people intended to become noblemen even by fabricating documents. Low-rank posts could be bought with money. In the 19th century, it was highly likely that those with economic abilities could become noblemen. Surely, it was not possible to reach a high-rank official even with the status of a nobleman in reality, yet a desire to assume a high-rank post and mark the sixtieth wedding anniversary may have set the trend of pyeongsaengdo.

Limit in Joseon and Pyeongsaengdo

Viewing these paintings that are filled with happiness from secular achievements in the Joseon period creates a bitter feeling. Pyeongsaengdorepresent Joseon in the 19th century when people shared a worldly standardized dream for a high-rank post and longevity. In the 19th century when these paintings were popular in Joseon, Europe moved forward due to the Industrial Revolution and the advancements of science and technology. However, those who rose through society with their freshly acquired status made the efforts to be incorporated into the existing system instead of seeking for a change in Joseon. The intellectual in Joseon had only one dream to become public officials by passing the State Examination without any other goal. Rather than approaching the Confucian scriptures with thoughtful and academic perspectives, they just learned and memorized them to prepare the test. Under these circumstances, it was difficult to expect sound criticism against the reality and movements towards a change. Joseon in the 19th century encounters a new era without an appropriate response to the changes of time. Pyeongsaengdoprovides us with an opportunity to ruminate on the lessons that we can gain from the passive attitudes to diversity and change.